Get Facts

Learn about key processes, policies and myths

client journey

Each person’s background, situation, preference, and needs are unique. Also, your journey towards survivorship may unfold in a varied and dynamic manner. Sometimes this may cause significant distress and unexpected disruptions to your life. Other times it may give closure and facilitate your healing process. At the NUS Care Unit (NCU), our care managers (CMs) are your partners in this journey.

At some stages of the process, NCU may be the only party in NUS empowered to access or provide certain support for you (e.g., accompaniment to investigation interview). The following five stages illustrate a typical client journey toward survivorship, but note that your journey may not progress as linearly as described below.

A general flowchart and description of the process can be found here.

You can reach out to us via walk-in, our Helpline, Help Email, Help Form, and/or through another source (e.g., CES, ORMC, SSMs, Residential Staff). Our Care Managers (CMs) will usually:

- Gather brief information about your situation and to make an initial assessment of your wellbeing;

- If you’d like, schedule an appointment at the earliest convenience, either electronically (via Zoom or phone call) or in person at a safe location on campus.

Our Care Managers (CMs), who are trained care professionals, will be ready to assist you at your first appointment. If this happens on campus, the CM would arrange to have the conversation in a safe and private location. If this happens virtually, the CM would check to see if you are in a safe and quiet space, and if the connection is stable for communication.

Our CMs will usually:

- Take the time to learn more about you, your situation and needs;

- Share more information about our suite of services to you;

- Explain the terms of the Care Manager-Client relationship and the limits to confidentiality so that you can make an informed choice on whether to register as a client of the NUS Care Unit (NCU).

The decision to receive help and support from NCU is yours, including when you choose to do so or when you may want to leave an existing partnership with us.

After registration, it is normal for you to have one or more sessions with a Care Manager (CM) throughout your time at NUS. Your CM may periodically check in on you. You may also contact your CM at any point in time to discuss your needs.

- For NUS investigations, an NUS Care Unit Care Manager (NCU CM) is empowered to accompany you during interview (i.e., be in the same room). A No-Contact Order (NCO) [3] may be issued to both the affected individual and the accused;

- For Police investigations, an NCU CM, can accompany you to the Police station, but will not be able to sit in the interview.

[1] Sexual Misconduct is a general term used in this Code of Student Conduct and Code of Conduct for NUS Staff to refer to a range of acts of a sexual nature committed against a person by force, intimidation, manipulation, coercion or without that person’s Consent, or at a point when that person is incapable of giving Consent.

[2] Section 424 of the Criminal Procedure Code states that: “every person aware of the commission of or the intention of any other person to commit any arrestable offence punishable shall … immediately give information to the officer in charge of the nearest police station or to a police officer of the commission or intention.”

[3] NCO is a No-Contact Order issued to one or more parties involved in disciplinary investigations or proceedings for a sexual misconduct offence. Persons subjected to NCO must not be subjected to any acts of retaliation, harassment, threats, intimidation and coercion.

NUS and Police investigations proceed independently of each other. After the completion of investigation, which usually involves one or more interviews with an investigation officer, NUS will submit their findings to the Office of Student Conduct (OSC) and Office of Risk Management and Compliance (ORMC). The Police will be similarly submit their findings to the Attorney-General’s Chambers (AGC). In general, the following will happen:

- For NUS cases, a Board of Discipline (BOD) or Committee of Inquiry (COI) may be convened to determine the sanctions, if any, to be meted out to the accused. Some NUS cases may be adjudicated at the Faculty/Department level. You may be invited to the hearing session and an NCU Care Manager (CM) is empowered to accompany you through this process.

- For Police cases, the AGC and court may require further information from you, before an outcome is determined.

Throughout this process, your CM will provide you with informational, practical and relational support. You will not be alone in this process.

Recovering from a traumatic incident is a gradual and individual process. Trauma symptoms may last from a few days to a few months, and typically fade gradually as time passes. Even if you think you have moved on, it is normal to feel occasionally troubled by painful memories or emotions, especially in response to certain triggers like the anniversary of the event.

The NUS Care Unit (NCU) will continue to provide you with quality care and support throughout your journey in NUS. From time to time, we may check in to review your needs. We may also organise and invite survivors like you to join specially curated activities.

As you approach the end of your journey at NUS, we will contact you once more. We would appreciate if you could complete a 10-minute feedback form to help us improve on our services.

We thank you for being kind and understanding towards our staff.

Coordinated End-to-End Care

journeying with NCU

1. Initial contact

You can reach us via our Sexual Misconduct Helpline, Help Email, Help Form, or through another on-campus resource (e.g., CES, ORMC, SSMs, Residential Staff).

Our Care Managers (CMs) will usually:

- Gather brief information about your situation and make an initial assessment of your wellbeing;

- Offer an appointment at the earliest convenience, either virtually or in-person at our centre.

You can also walk-in. We are at B1, University Health Centre (UHC). We are open on Mon – Fri (excl. public and university holidays), 9 AM to 5 PM.

2. registering as our client

At your first appointment, our CMs will usually:

- Take the time to learn more about you, your situation and needs;

- Share more information about our services;

- Explain the terms of the CM-Client relationship and the limits to confidentiality so that you can make an informed choice before registering as our client.

The decision to receive help and support from us is yours, including when you choose to do so or when you may want to cease receiving support from us.

After registering with us, it is normal for you to have one or more sessions with a CM throughout your time at NUS. Your CM may periodically check in on you. You may also contact your CM at any time to discuss your needs.

3. reporting & investigation

There are several channels for filing a report of alleged sexual misconduct1. If it involves an NUS student, you can report to the Campus Emergency & Security (CES). Reports about NUS staff will be attended to by the Office of Risk Management & Compliance (ORMC). You may also file a police report.

- For NUS investigations, our CMs are empowered to sit in with you during interviews. A No-Contact Order (NCO)2 may be issued to you and the accused.

- For Police investigations, our CMs can accompany you to the Police station, but will not be able to sit in the interview.

[1] If the alleged misbehaviour is an arrestable offence under Sec 424 of the Criminal Procedure Code, NUS may be obligated to file a police report. This will be discussed with you in advance and NUS will ensure that you are supported throughout the process.

[2] An NCO is a No-Contact Order issued to one or more parties involved in disciplinary investigations or proceedings for a sexual misconduct offence. Persons subjected to NCO must not be subjected to any acts of retaliation, harassment, threats, intimidation and coercion.

4. Adjudication

NUS and Police investigations proceed independently of each other. After the completion of investigation, which usually involves one or more interviews with an investigation officer, NUS will submit their findings to the Office of Student Conduct (OSC) and ORMC. The Police will similarly submit their findings to the Attorney-General’s Chambers (AGC). In general, the following will happen:

- For NUS cases, a Board of Discipline (BOD) or Committee of Inquiry (COI) may be convened to determine the sanctions, if any, to be meted out to the accused. Some NUS cases may be adjudicated at the Faculty or Department level. You may be invited to the hearing session and our CM is empowered to accompany you through this process.

- For Police cases, the AGC and court may require further information from you, before an outcome is determined.

Throughout this process, your CM will provide you with informational, practical and relational support. You will not be alone in this process.

5. survivorship

Recovering from a traumatic incident is a gradual and individual process. Even if you think you have moved on, it is normal to be occasionally troubled by painful memories or emotions, especially in response to certain triggers like the anniversary of the event.

NCU will continue to provide you with quality care and support throughout your journey in NUS. We may check in with you periodically to review your needs.

As you approach the end of your journey at NUS, we will contact you once more for a closing session.

We thank you for being kind and understanding towards our staff.

policies and regulatory frameworks

NUS actively seeks to improve its existing policies and regulatory frameworks to promote community safety. For example, NUS implemented several interventions such as renewed disciplinary framework, course on respect and consent, enhancements to campus physical security following recommendations from a review committee on sexual misconduct as well as feedback from the NUS community. Most students (85%-96%) believe that these interventions contributed positively to campus climate and safety3.

[3] NUS Care Unit 2020 Student Survey on Sexual Misconduct Experiences. National University of Singapore.

nus policies

The Policy on the Protection of Staff and Students Against Sexual Misconduct provides an integrated approach for managing cases of sexual misconduct in NUS, and provides a system for reporting, investigation and decision-making.

Other useful documents include:

For more information about student and staff discipline, including disciplinary framework and sanctions, visit the NUS student portal or NUS staff portal (NUSID/staff ID required).

police investigation and court processes

common myths

Rape myths, assumptions, and stereotypes are harmful. These false statements not only discourage survivors from speaking up but also hinder our community from effectively dealing with and eradicating sexual misconduct.

| Myth | Fact |

|---|---|

| Sexual assault is an act of lust and passion that can’t be controlled. | Sexual assault is about power and control and is not entirely motivated by sexual gratification [2] |

| Sexual assault is most often committed by strangers. | 8 out of 10 cases of sexual violence involve perpetrators who are known to the survivor, usually in the capacity of an acquaintance or a current/former intimate partner [1]. |

| A person cannot sexually assault their partner or spouse. | Nearly 1 in 10 women have experienced rape by an intimate partner in their lifetime [3]. With the passing of the Criminal Law Reform Act in 2019, there is no longer legal immunity for marital rape in Singapore today [4] |

| Sexual assaults most often occur in public or outdoors. | 55% of rape or sexual assault victimisations occur at or near the survivor’s home, and 12% occur at or near the home of a friend, relative, or acquaintance [5]. |

| If a person goes to someone’s room, house, or goes to a bar, they can’t claim to have been raped or sexually assaulted because they should have known not to go to those places. | This “assumption of risk” wrongfully places the responsibility of the offender’s actions with the survivor. Even if a person went voluntarily to someone’s residence or room and consented to engage in some sexual activity, it does not serve as a blanket consent for all sexual activity. |

| Wearing revealing clothing, behaving provocatively, or drinking a lot means the survivor was “asking for it”. | The perpetrator selects the survivor. The survivor’s behaviour or clothing choices do not mean that they are consenting to sexual activity. |

| It’s not a big deal to have sex with a person while they are drunk, stoned or passed out. | If a person is unconscious or incapable of consenting due to the effects of alcohol or drugs, they cannot legally give consent. Without consent, it is sexual assault. |

| If a woman doesn’t report to the police, it wasn’t sexual assault. | Just because a survivor doesn’t report the assault doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. Only about 3 in 10 survivors report their experience of sexual violence to the police [6]. |

| If a person didn’t scream or fight back, it wasn’t sexual assault. | When a person is sexually assaulted, they may become paralysed with fear and be unable to fight back. The survivor may be fearful that if they struggle, the perpetrator will become more violent. If the survivor was under the influence of alcohol or drugs, they may have been incapacitated or unable to resist. |

| People that have been sexually assaulted will be hysterical and crying. | Everyone responds differently to trauma – some may cry while others will not show any emotions [7]. |

| If the person is unable to recall details and facts in proper order, they are lying and it didn’t actually happen. | Shock, fear, embarrassment and distress can all impair memory. Memory loss is a common result of trauma, alcohol and/or drugs. Many survivors also attempt to minimise or forget details of the assault as a way of coping. |

| Men cannot be survivors of sexual violence. | Sexual violence is blind to gender and affects both men and women [1]. Gender stereotypes of masculinity and social stigma of having been victimised are key reasons why there is proportionately greater underreporting of sexual violence in men than women [8]. |

| Getting help is expensive for survivors of assault. | Services such as counselling and advocacy are offered for free or at a low cost by sexual assault service providers. |

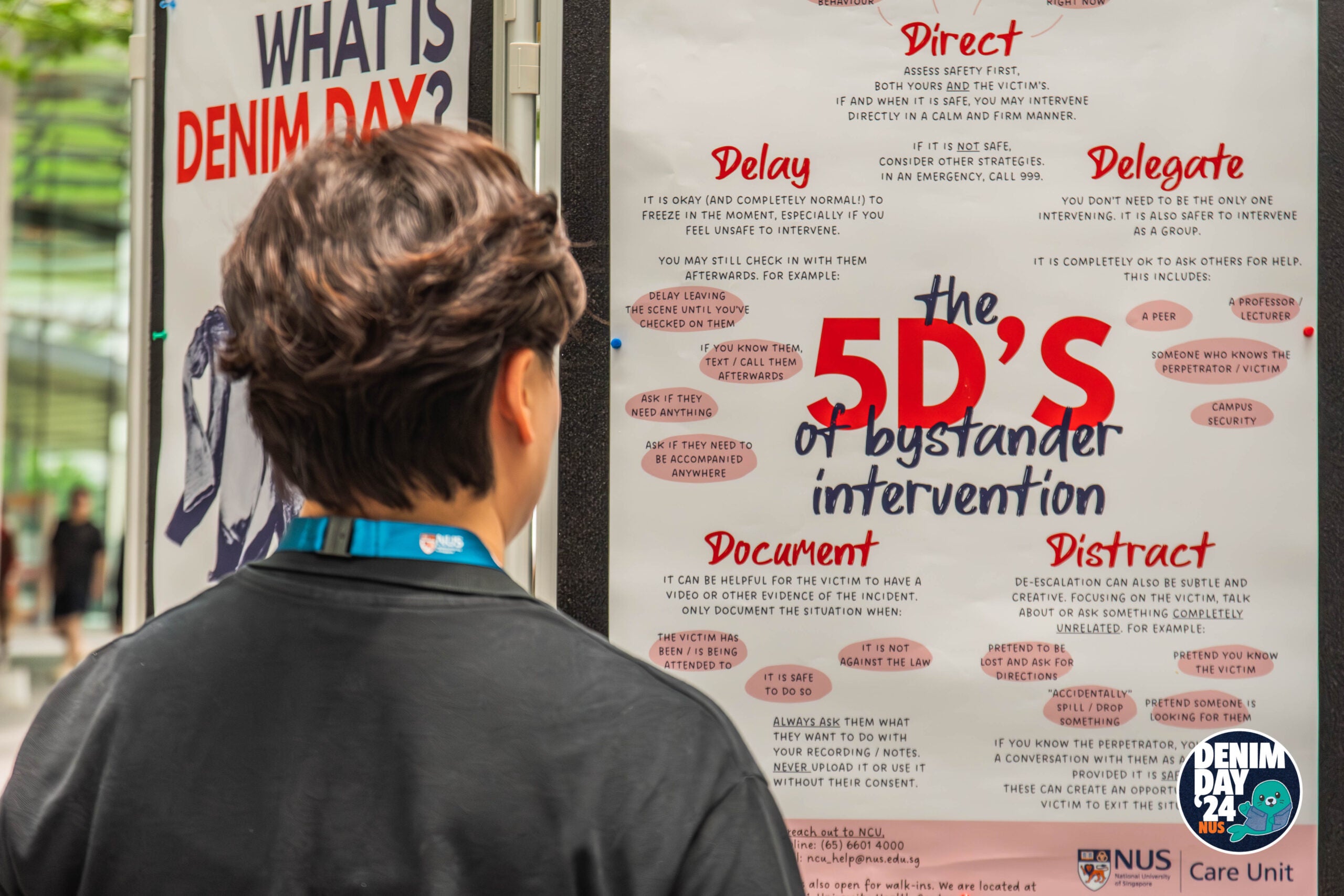

| There is nothing we can do to prevent sexual violence. | There are many ways you can help prevent sexual violence including intervening as a bystander to protect someone who may be at risk. |

References

[1] NUS Care Unit 2020 Student Survey on Sexual Misconduct Experiences. National University of Singapore.

[2] Groth AN, Burgess AW, Holmstrom LL. Rape: Power, anger, and sexuality. AM J Psychiatry. 1977;134(11):1239-43.

[3] CDC. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey 2010 Summary Report.

[4] Ministry of Home Affairs. Commencement of Amendments to the Penal Code and Other Legislation on 1 January 2020 [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Nov 24]. Available from: https://www.mha.gov.sg/newsroom/press-release/news/commencement-of-amendments-to-the-penal-code-and-other-legislation-on-1-january-2020.

[5] Marcus B, Christopher K, Lynn L, Michael P, Hope S-M. Female Victims of Sexual Violence, 1994-2010. 2013 Mar.

[6] Teng A. Number of reported rape cases up 75% in past five years, Courts & Crime News & Top Stories – The Straits Times [Internet]. The Straits Times. 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/courts-crime/number-of-reported-rape-cases-up-75-in-past-five-years.

[7] Fanflik P. Victim Responses to Sexual Assault: Counterintuitive or Simply Adaptive? 2007 Aug.

[8] Stemple L, Meyer IH. The sexual victimization of men in America: New data challenge old assumptions. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6):e19.

- Home

- Get Facts

NUS Care Unit

- University Health Centre,

- 20 Lower Kent Ridge Road,

- #B1-09, Singapore 119080

- For general enquiries:

- +65 6601 3155

- ncu_admin@nus.edu.sg

- Office hours:

Monday - Friday: 9am - 5pm - Website Feedback